Review

A Nose and Three Eyes

by Ihsan Abdel Quddous’s

Five or six years ago, I was reading Ihsan Abdel Quddous (1919–1990) with my Arabic teacher and thought of writing an article about him in English, but I found only one translation on Amazon. I was puzzled. Why had one of the best-known Egyptian novelists gone untranslated? Had leftist Egyptian intellectuals steered Arabists away from him, dubbing him an aristocratic right-winger? Had he been unfairly stereotyped as a novelist who wrote only for teenage girls? Or had he simply been unlucky in the quixotic business of English publication? It was unclear. READ MORE

Shahrazad's Gift

by Sherine El-Banhawy

WITH A SHARP EYE for detail, Gretchen McCullough’s Shahrazad’s Gift is a short-story collection that delves into Cairo’s lively, chaotic daily interactions, capturing residents’ richly colorful experiences from diverse backgrounds and lifestyles as they clash and blend. From Batilda, a scissor-throwing Swedish belly dancer, to Vartan, the incompetent Armenian dentist, the stories pulse with the lives of expatriates, tourists, refugees, or locals seen in their most vulnerable states, through dialogue that crackles with life that is at times both absurd and deeply human.

The collection culminates with two stories forming a novella whose quirky, fun characters are so intriguing that they segue into McCullough’s debut novel. One such character is the protagonist Gary, an American professor who encapsulates his yearning for Cairo: “I felt myself weakening. I missed the idiosyncrasies of Egypt. The unpredictability and spontaneity of the place.” READ MORE

THE SECRETS OF FOLDER 42

by Abdelmajid Sebbata

A knight’s tour of a chessboard, crisscrossing through continents and time!

The Secrets of Folder 42, by Abdelmajid Sebbata, translated by Raphael Cohen, published by Banipal Books (2024), is a literary thriller which fuses collage and straightforward narration with two story lines in the United States, Morocco and the Russian capital, Moscow. Already recognized in Morocco for his literary achievements, The Zero Hour (2017) was awarded the Moroccan Book Award. Striking a fine balance between the experimental novel and a thriller and between reality and literature, I felt that the author, himself, will just keep pulling doves out of his sleeve. Reminiscent of Luigi Pirandello’s “Six Characters in Search of an Author,” Sebbata’s novel, The Secrets of Folder 42, his third novel, was shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2021. READ MORE

An Unlasting Home

(World Literature Today, 2022)

MAI AL-NAKIB’S debut novel, An Unlasting Home, circles around the complicated family legacy of her main character, Sara, an academic with Arab parentage, who grewup in Kuwait but was educated in American schools and universities. With her parents\ and grandparents dead, Sara returnsto Kuwait to the family house, to reckon with her “bifurcated” identity. The title, AnUnlasting Home, is taken from Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and refers to wanderers, like birds, who buildnests, “an unlasting home under the eaves of men’s houses.” The book is an ambitious family epic with a historical sweep, an elegy to grandmothers and mothers who were forced from their original homes by personal or political circumstances in the Middle East to build nests elsewhere. READ MORE

Warda: A Novel

(The LA Review of Books, 2021)

MANY OF SONALLAH IBRAHIM’S novels explore how former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser’s version of socialism was “a dream.” Yet Warda, originally published in Arabic in 2000, examines the fate of the Dhofar Liberation Front, an Arab Marxist movement that sought to drive the British out from Oman and Yemen in the 1960s and 1970s. This political movement is intertwined with the Egyptian narrator’s personal dreams and memories of Warda, the nom de guerre of an Omani activist with whom he fell in love at Cairo University in the late 1950s. Informed by impressive research, the novel tells the little-known story of the Dhofar Liberation Front, an eclectic mix of Arab intellectuals, herders, and tribal folk who were initially drawn to the group because they desired a more equitable society. READ MORE

The Girl with Braided Hair

(World Literature Today, 2020)

RASHA ADLY’S NOVEL The Girl with Braided Hair tells parallel love stories, with one set in contemporary Egypt, post-2011 uprising, and the other during Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt. The main character in the present, Yasmine, an art history professor, is intrigued by a painting from the French occupation—and the novel revolves around solving the mystery of the Egyptian girl’s identity in the painting and the story of the painter, who was not listed in Napoleon’s official retinue.

The basic premise of the novel—the quest for the “lived story” behind a historical object—is a deceptively promising one. Abd Al Rahman Al-Jabarti’s The Marvelous Compositions of Biographies and Events is certainly the right historical source for this novel since he witnessed the French invasion of Egypt. Writing historical fiction is a tightrope act for a writer, balancing between historical fact and storytelling with characters who should seem as flawed and human as our friends and neighbors. READ MORE

Ice

(World Literature Today, 2019)

IN 2016 I CHATTED with Sonallah Ibrahim about his then-new novel, Berlin 69.I asked him: “Did your experience in East Germany and Russia (1969–74) give youa useful perspective on Nasser’s version ofsocialism?” He replied: “The dream was fantastic, but it remains a dream.” His new novel, Ice, translated by Margaret Litvin, takes a scalpel to the “fantastic dream” of communism through the eagleeyes of a wry Egyptian narrator who hascome to study in Russia. The novel echoessome of the themes of Berlin 69: coping with paranoia and the fear of intelligenceservices, nostalgia for Egypt, transient relationships with foreign women, the hunt for scarce commodities, and a corrupt partyelite. Unlike Berlin 69, however, the structure of Ice mimics a diary—and depends onthe writer’s telegraphic but carefully honedstyle, which gives the reader a sense of the chilling, grim texture of daily life in Soviet Russia in the 1970s. Ibrahim lived in Moscow during a crucial period in Egypt’s history,following the 1967 defeat and Egypt’s 1973 victory over Israel.READ MORE

Review: The Ruins of Ani by Krikor Balakian

(the literary review, 2018)

In the late eighties, I was teaching at the Uskudar Girls School in Istanbul, and I went on a trip with my partner at the time to Kars, the largest town on the Turkish border, which felt a little like the Wild, Wild West. We visited the ruins of Ani nearby, enclosed by barbed wire and guarded by on-edge soldiers. I saw those majestic medieval churches on the plain without much knowledge of their historical context or why they had been cordoned off by the Turkish state. More than thirty years later, The Ruins of Ani, by Krikor Balakian, translated by his grand-nephew, Peter Balakian with Aram Arkun, provides much in the way of historical perspective on the site. The Ruins of Ani is at once a sophisticated tour guide for travelers, an important archaeological document, and a blitz of resistance in the face of attempted erasures; we are all lucky that the priest and author (the elder Balakian) described the ruins and excavations at Ani in 1909 before the Armenian genocide in 1915. READ MORE

A Review of Thirty Days by Annelies Verbeke

(the literary review, 2018)

In March 2003, thousands of protestors swelled into Tahrir Square, enraged over America’s incursion into Iraq. I was looking out the window of my office at the American University in Cairo–alarmed to see riot police, clad in black, running in formation down a main street. Suddenly, Falak Farah, the chair of our department, who had survived the Lebanese civil war, stood in the doorway: “You better get a ride home. It might turn into a mob.” I remember how frightened I was. The crowd was beating up foreigners who ventured into the melee. More recently, in Chemnitz, Germany six thousand demonstrators took to the streets, arms raised in Nazi salutes, furious over Angela Merkel’s immigration policy. The following day, a huge counter-protest responded with: “Heart Not Hate.” On the nightly news, there are also the recurring images of refugees from Africa and the Middle East, wrapped in foil blankets at ports. More tragic, still, are tiny, READ MORE

A Review of Lost Places by Cathryn Hankla

(the literary review, 2018)

Samuel Morse’s invention of the telegraph revolutionized communication in 1844. Yet we are now living in a world where messages are travelling faster than the click of a button with email, SMS, Facebook and Twitter, etc. At times this is mighty convenient, especially if you are miles away from the action or living on another side of the world, like me, in Cairo. However, the ease of modern communication often elevates and dignifies the unconsidered word and the impulse to simplify. The artfulness of Cathryn Hankla’s accomplished collection of essays, Lost Places: On Losing and Finding Home, is precisely that it bucks the current zeitgeist of communicating in a reductionist, binary style: Yes/No; Tremendous/Terrible; Good/Bad; Like!/Unfriend. The experience of reading Hankla’s essays is very much like the pleasure of taking a rambling stroll in the forest, or a leisurely lunch with a close friend, ruminating on the complex, mysterious nature of human existence. READ MORE

A Review of Adua by Igiaba Scego

(the literary review, 2017)

Adua, by Igiaba Scego, translated by Jamie Richards, is a lyrical novel that describes the cultural alienation of Somalis living in Italy, both in the present and during the 1930s under the reign of Mussolini. While Scego’s family is originally from Somalia (her parents fled the country because of a coup d’etat in 1969) the novel is not a linear, autobiographical tale; instead, the author merges African fable and folklore, family anecdotes, and a sophisticated knowledge of literature and cinema to explore themes of colonialism, racism, and power. Adua centers on the idea of a split identity. In the opening chapter, the main character, Adua, who is herself from Somalia, is confused about which country she should call home, Somalia or Italy. Her friend, Lul, has decided to repatriate to Somalia, yet Adua wonders if she wants to return. READ MORE

A Review of A Greater Music by Bae Suah

(the literary review, 2016)

Reading Bae Suah’s novel, A Greater Music, is much like the experience of listening to the concertos of Beethoven. I listened to Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 2, mentioned in the novel, and heard a fluty playfulness in the music that does not match the pensive mood in the prose; however, the novel resonates with a serious, philosophical intensity. Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3, on the other hand, is simply grand. In A Greater Music, Suah’s young narrator muses upon many of the grand, existential themes of life: love, friendship, betrayal, freedom, memory, and death. The coming-of-age novel revolves around a series of dream-like vignettes of a Korean narrator who has come to live in Germany: she is initiated into love and art by the mysterious, cultured M., a music aficionado. Suah, the writer, herself, is a translator, living in Berlin, translating German literature into Korean – and one can see the strong influence of German culture on her writing. READ MORE

A Review of Margaret the First by Danielle Dutton

(the literary review, 2016)

Margaret the First was not a queen, like Katherine of Aragon or Ann Boleyn. But she could be considered an early queen in the history of women’s literature: Margaret Lucas Cavendish, a 17th century Duchess, the daughter of Royalists, fled to France when Charles I was overthrown. Cavendish was an accomplished writer and thinker who published poems, philosophy, plays and utopian science fiction. Danielle Dutton’s novel, Margaret the First, published by Catapult, is a literary page-turner, which explores Cavendish’s adventurous life, weaving historical details into a spool of crafted, poetic prose. Margaret the First is Dutton’s third book, her second novel, and a natural outgrowth of her earlier work. Attempts at a Life, (Tarpaulin, 2007), was a collection of prose pieces, experimenting with genre. READ MORE

A Review of Lay Down Your Weary Tune by W.B. Belcher

(the literary review, 2015)

After regaling us with entertaining anecdotes about his life as a screen writer in Hollywood, the late Gill Dennis threw out a curve ball: “What was your greatest moment of shame?” He was teaching a workshop at the Squaw Valley Writers’ Conference called “Finding the Story.” Dennis co-wrote the screen play Walk the Line (2005) with James Marigold about the life of the famous singer, Johnny Cash, the son of a sharecropper from Arkansas. Dennis described to us how he “found the story” for the screen play through a series of frank, personal interviews with Johnny Cash, and those who knew him well. Writing truthful biographies about live subjects is a tricky, volatile business. READ MORE

A Review of The Perception of Meaning by Hisham Bustani

(the literary review, 2015)

Hisham Bustani’s third collection of fiction, The Perception of Meaning, translated by Thoraya El-Rayyes, is like a house of mirrors at a carnival, reflecting the distortion, absurdity, and maladies of a modern world that worships technology and destroys nature. The book was the co-winner of the prestigious King Fahd Center for Middle East Studies Translation of Arabic Literature Award for 2014 at the University of Arkansas. Bustani’s work is experimental, literary fiction with a razor edge, slicing the tops off of familiar myths, tales, legends, and then, transforming them into visceral, grotesque fables. Hisham Bustani, known in the Arab world for his contemporary, “surreal” view, draws widely upon film, history, politics and literature for inspiration in his flash fiction. READ MORE

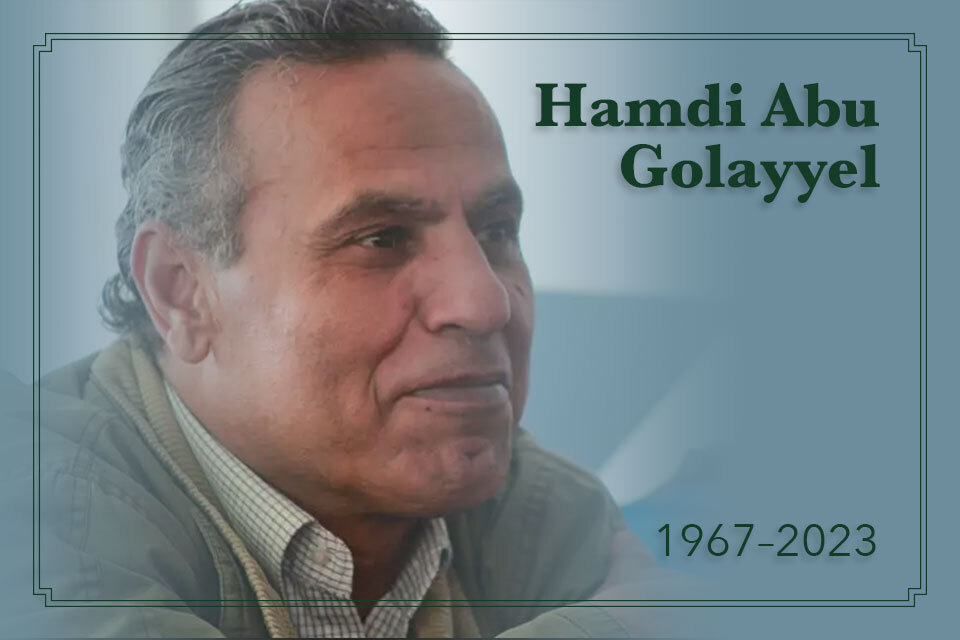

Hamdi Abu Golayyel: A Gifted Storyteller with an Eye on Rogues and Tall Tales

(World Literature Today, 2023)

Hamdi Abu Golayyel (b. 1967) was a gifted storyteller who fused Egyptian oral storytelling, myth, and folklore to tell the tales of marginalized and working-class communities in Egypt. He died on June 11, 2023. He was only fifty-six. I did not know him personally but reviewed the translation of his recent novel, The Men Who Swallowed the Sun, for the magazine Banipal. In one of those ironic twists of fate, I had asked a journalist friend for his phone number because I wanted to meet him. I received the number, but months passed and I didn’t follow up on the impulse—sudden death is a poignant reminder of the precariousness of our existence on this earth. Apparently, Abu Golayyel was as colorful in real life as the characters in his work. READ MORE

Looking for Dragon Smoke:Essays on Poetry

(White Pine Press, 2019)

At age ninety-two, Robert Bly is releasingsimultaneously his Collected Poems and hiscollected essays, Looking for Dragon Smoke,which would be ominous if not for the sheerabundance of his life’s work. In the lattervolume, we have his sixteen most importantessays, written from 1977 to 2005, thoughmostly in the 1980s and 1990s. The bookis divided into four sections, but the essaysreally fall into only two categories: essays onpoetry and poetics and essays on specificwriters, mostly poets.

The best of the discussions about writersare probably the ones on Rilke, Machado,and Thoreau. In these, Bly goes beyonddemonstrating the application of his poeticsto the work in question, which is interesting in itself and which often tells us as much ormore about Bly as it does about the work. READ MORE

A Dream Called Home

(Atria Books, 2018)

REYNA GRANDE shares her experiences as an undocumented immigrant from Mexico who, at age nine, accompanied by young siblings and a coyote, succeeded on her third attempt to cross the border near Tijuana. Her life story is a fascinating one, not only because of her willingness to be absolutely frank about her feelings and perceptions but for the impact the immigration experience has had on generations of families and the family structure. When Grande was barely a year old,her father crossed the border to “El Otro Lado” (The other side) to find a way to earn money to send back to his family indesperately impoverished Iguala, Guerrero.Later, when Grande was five, her mother also left to join her husband inCalifornia. Feeling abandoned in Iguala, Reyna was left in the care of relatives who were often cruel. When she was nine, her father was able to send money for the passage to “El Otro Lado.”READ MORE

Praise for Gretchen 's Books

Few literary works have dealt with the Egyptian Revolution in 2011 as well as this novel did, whether in Arabic or English, by the American author, Gretchen McCullough. McCullough survived the events of the uprising at Tahrir Square—the novel focuses on a group of expatriates who stayed in the country. It would appeal to the lovers of detective novels as much it would appeal to wacky fantasy lovers and uses literary humor, which is emphasized in an alleged message by Colonel Muammar Qaddafi of Libya. The reader might share the author’s sarcasm about overwhelming globalization and the American lifestyle, whose advocates want to impose it on the rest of the world. Wait! It’s not just that. The reader might get free lessons in the art of cooking.

—Sonallah Ibrahim, Egyptian novelist